109:

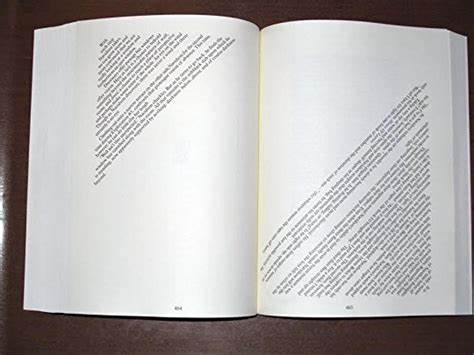

The text is about nothing – always about nothing. Nothing is what keeps the text in play by rendering it irreducibly open and in/finitely complex. The nothingness haunts the text marks its border by exceeding it. This excess is the siteless site where difference endlessly emerges.

113:

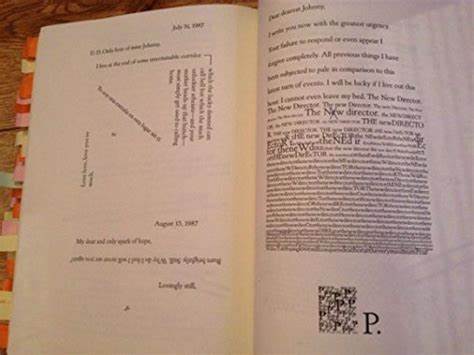

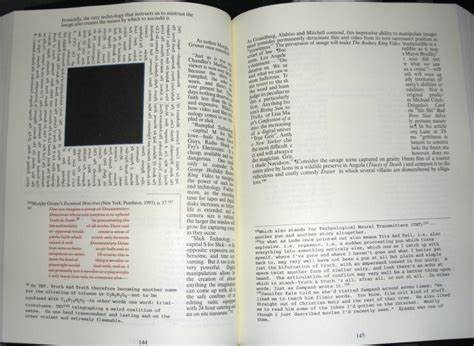

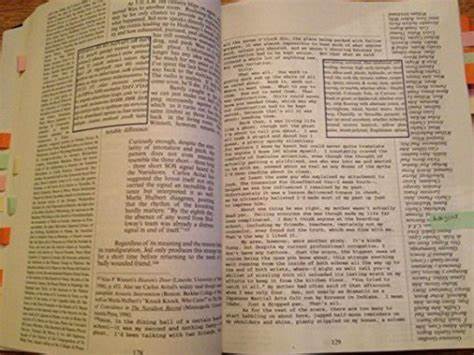

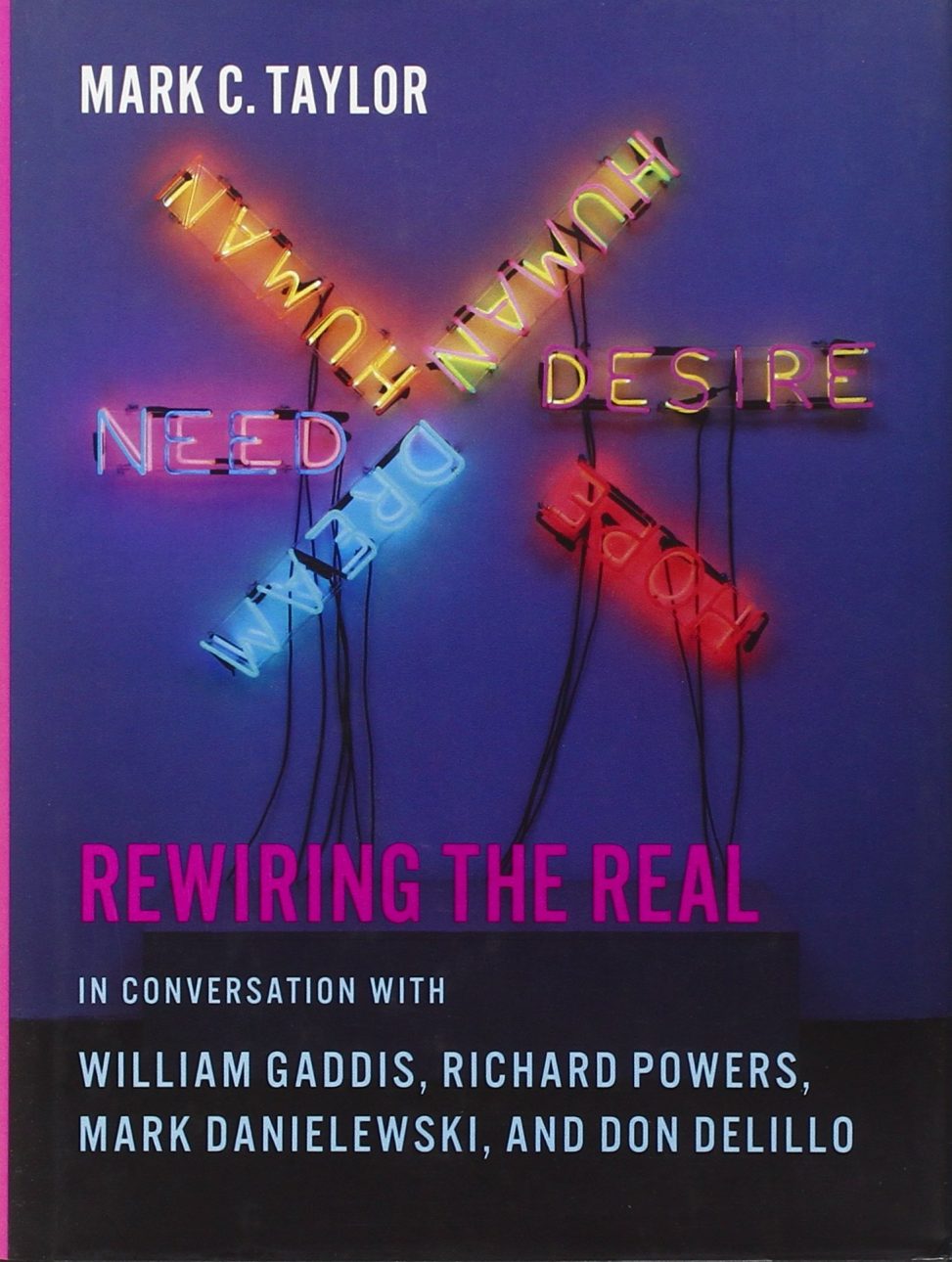

The complexity of the work is compounded by a graphic design that enacts or performs the ideas that the multiple authors and characters explore.

115:

Though Danielewski’s name appears on the cover and copyright page, the title page indicates that Zampano is the author and Johnny Truant has contributed an introduction and extensive notes.

115:

Zampano turns out to have been a blind recluse who wrote an extensive commentary on The Navidson Record.When Johnny Truant, whose name suggests that he is a Johnny-come-lately, and his friend Lude, whose real name is Harry, discover Zampano’s body in his crypt-like apartment, Johnny inherits a monstrous truck that contains pages and pages of the old man’s reflections on the film. The twenty-something-year-old kid … assumes the onerous responsibility of organizing Zampano’s ramblings into something resembling a coherent narrative. Johnny appends notes explaining his editorial procedures and adding his own observations and reflections, which are so extensive that they eventually overwhelm Zampano’s text.

118:

This book about a book layers text upon text. In addition to Navidson’s film, Zampono’s commentary, and Johnny’s commentary on the commentary, House of Leaves includes an elaborate textual apparatus citing scholarly comments, articles, and books either about the text or relevant to it.

118:

Moreover, though many of the authors cited are real and the articles and books noted have actually been published, many of the passages quoted are made up, and pages referenced are either incorrect or do not exist.

119:

Every time the reader images a new way to interpret the text, he turns the page only to discover a footnote or footnote to a footnote in which some “author” has anticipated his analysis.

123:

One afternoon, while working as an apprentice at the tattoo shop, Johnny suddenly has the strange feeling that “something’s really off. I’m off.” What makes this experience all the more unsettling is that “nothing has happened, absolutely nothing” (26). … he reports …. “Though my fingers still tremble and I’ve yet to stop choking on large irregular gulps of air, as I keep spinning around like a stupid top spinning around on top of nothing, looking everywhere, even though there’s absolutely nothing, nothing anywhere” (27).

125:

As speech emerges from silence, so writing emerges from a void that is never completely erased. Yet precisely this emptiness is what much – perhaps most – writing is designed to avoid. … Above all else, stories are supposed to protect us from the emptiness, meaninglessness, absence and the nothingness they nonetheless harbor. All such efforts, however, prove futile because nothing can be a-voided; there can be no story without the haunting emptiness it is written to fill.

191:

People, things, and events proliferate in narratives and counternarratives that simultaneously connect and disconnect, until everything becomes somewhat chaotic. The only thing that seems to tie it all together is waste. With every turn of the page, there is more waste – wasted lives, wastebands, wasted bodies, limbs, sewers, dumps, landfills, junk, trash, garbage, shit – all kinds of shit – and, of course, radioactive nuclear waste. There are also other less recognizable and predictable forms of waste – games, art, and religion.

195:

Underworld is big – too big – and messy. By any reasonable measure, it is excessive – 827 pages! It seems to fall apart more often than hang together.

196:

As pages turn and stuff keeps piling up, readers are left to sort through the historical and cultural debris of the latter half of the twentieth century in the hope of finding patterns where there seems to be nothing but noise.

199:

The temporal organization of Underworld is as complex as its spatial structure. DeLillo’s counternarrative is not straightforward but consists of multiple narratives and counternarratives joined by tangled loop-lines. The events he recounts all take place during the four decades from the summers of 1951 and 1952 and the summer-spring of 1992.

201:

It is too easy to set up a simple opposition between a modernist utopia and a postmodernist dystopia because the liminal spaces Delillo explores are too complex to be contained by such sharp boundaries.

Images sourced from google images:

Leave a Reply